Tens of thousands of years ago, humans lived in and explored caves in very different ways to how we do it today. They may not have owned modern flashlights, but it doesn't mean they dwelled in complete darkness.

To try and learn more about ancient cave-dwelling life - from the painting of rock art to socialization - a team of researchers has now recreated three common types of ancient lighting techniques: torches, grease lamps, and fireplaces.

All three were used back in the Upper Paleolithic period starting about 50,000 years ago; the team then put their lights into practice, exploring the effects of these illumination sources inside the Isuntza 1 Cave in Spain.

"Humans [..] need light to enter the deep parts of caves, and their visits to those places depend on the physical characteristics of their lighting systems," write the researchers in their paper.

"The luminous intensity, radius of action, type of radiation, and color temperature of the light determine the perception of the environment and the human use inside (such as the execution of art, funerary activities, and cave exploration)."

The researchers equipped themselves with eight different lights modeled on archaeological artifacts: five torches made from ivy, juniper, oak, birch and pine resins, two stone lamps burning animal fat (cow and deer bone marrow), and a small, static fireplace made from oak and juniper wood.

Measurements were taken inside the cave network – two wider, open spaces and a tunnel – including the brightness of each lighting source, how long each one lasted, and the temperatures they produced.

The torches made from wooden sticks seemed to work best for exploring and moving around: they were reasonably long lasting (averaging out at 41 minutes), they projected light in all directions (almost six meters or 20 feet), and could easily be relit by waving them from side to side. However, they also produced a lot of smoke.

The grease lamps worked best for keeping smaller spaces illuminated for a longer period of time, burning for over an hour without much smoke – although their light only stretched about half as far as the light from the torches.

As for the fireplace, it had to be put out after 30 minutes because of the amount of smoke it produced – though it did illuminate a distance of 6.6 meters (21.7 feet). The fire would need to be in a place with good ventilation, the researchers say, or be large enough to produce its own convection currents.

These experiments give us a good idea of the sort of constraints that humans in the Upper Paleolithic would have been under in terms of exploring tunnels, living in deeper parts of caves, and indeed producing cave art.

As Ars Technica reports, some experts have suggested that ancient cave art was designed specifically for a flickering, unsteady source of illumination – and may even have been painted to create the illusion of movement as the light wavered.

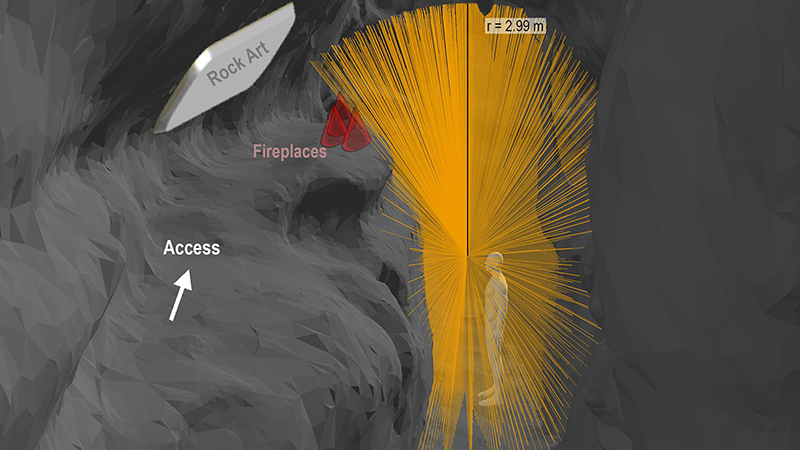

That's not a detail this new study goes into, but the team did run a simulation using their lighting measurements to see how these torches, lamps, and fireplaces would work in the Atxurra cave in Spain, well known for its Paleolithic-era artworks.

It seems that static fireplaces would have been needed to illuminate all of the art on the cave walls, as the light from torches and lamps wouldn't have stretched far enough.

The team behind the new study sees this as just the start of this type of investigation – more types of lighting sources and fuels can be tested, and simulated in more types of settings, to better understand how our ancestors spent their time in caves.

"Our experiments on Paleolithic lighting point to planning in the human use of caves in this period and the importance of lighting studies to unravel the activities carried out by our ancestors in the deep areas of caves," write the researchers.

The research has been published in PLOS One.

No comments:

Post a Comment